A multi-year study completed by local researchers found that Texans who live nearest to oil refineries are at significantly higher risk of getting cancer.

The study, recently published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, was conducted by a team of physicians, scientists, and students at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston. The researchers used Texas Cancer Registry and Census data from 2001 through 2014, to compare rates of cancer of people within 30 miles of 28 active Texas oil refineries.

The study found a clear correlation between distance from an oil refinery and rate of all cancer types. Of the more than 800,000 cancer patients living in Texas during that period, 34 percent lived in close proximity to an oil refinery. Patients living within 10 miles of refineries were most likely to have an advanced cancer diagnosis, compared to those who lived 21 to 30 miles away.

More Houston News

Previous studies across the globe have shown that toxins associated with oil-refinery processes pose a high risk of cancer to nearby residents. Cancer-causing pollutants most commonly associated with refineries include benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylene compounds. As oil production in the United States has soared — 18.8 million barrels per day — and with Texas as the country’s leading producer, public health concerns have been raised on behalf of those living and working near oil refineries.

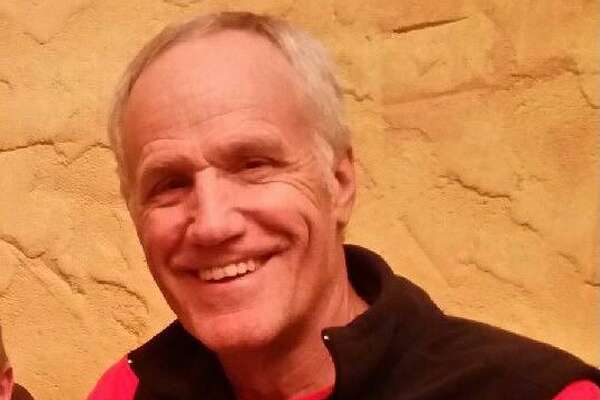

One of the co-authors of the study, Stephen Williams, chief of urology at the medical branch and a professor of urology and radiology at UTMB, hoped the findings would leverage a collaborative effort with some of the state’s oil refineries to determine causes of illnesses among their employees. The team of researchers plans to apply for a grant from the Cancer Prevention Research Institute of Texas to further investigate their findings.

“There have been studies that have been done, particularly by the individual oil refineries themselves with their own employees, and there are data to suggest increased cancer among those particular individuals when they compare to the general population,” Williams said. “But these have either been done not recently, and then (it) also begs the question of whether or not they would allow investigators such as ourselves to look into this a little bit further.”

Williams added there were limitations to using ZIP code and county-level Census data for the study that prevented researchers from gleaning important factors — such as an individual’s job and health history that might contribute to a cancer diagnosis.

“Obviously, (individual patient data) are extremely important confounders when we're trying to determine whether there's a cause and effect,” he said.

Socioeconomic factors also played a role in determining which populations were most at risk from proximity to oil refineries. The UTMB study found that individuals living within 10 miles of refineries between 2010 and 2014 were more likely to have incomes below the poverty level. Those individuals were significantly more likely to have an advanced cancer diagnosis.

For environmental advocates, the results of the UTMB study were hardly surprising. Several Houston-area refineries were found to have skirted Environmental Protection Agency regulations on releasing toxic pollutants like benzene, according to an analysis released by the nonprofit Environmental Integrity Project in February.

“We've tracked refinery emissions and done enforcement work and also spent a lot of time looking at the permits for these refineries,” said Ilan Levin, associate director of the Environmental Integrity Project. “They’re allowed by law in their permits to release very dangerous carcinogens like benzene and other dangerous (pollutants).”

The American Petroleum Institute, a trade association representing the nation’s oil and gas industry, noted in a statement that oil producers employ thousands of scientists and engineers who are working to safely refine and deliver energy in “cleaner ways.”

“It is our top priority to protect the safety of the communities and environment in which we operate, and we follow industry best practices, standards and government regulations to ensure strong environmental and public health protections,” said Uni Blake, a public health toxicologist for the industry group. “This includes precautionary measures that minimize or mitigate exposures from substances that have the potential to affect health and safety.”

While the study did not connect the ZIP code data to specific refineries, it does include heat maps of Texas showing where cancer diagnoses are most prevalent by way of their geographic proximity to oil wells. Notably, these maps show annual rates for lymphoma and cancers of the bladder, breast, lung, prostate and colon were clustered near many refineries in southeast Texas, including several in the Houston area. Williams, however, noted that there are many other petrochemical industrial complexes in these areas that could contribute to these illnesses.

“(The study) is hypothesis generating,” Williams said. “It stimulates further research questions. And it really, I believe, provokes further individual level assessments, where whether we're looking at the epidemiologic or the individual level, looking at specific toxicology field work, or the soil or environment in these areas itself.”

nick.powell@chron.com