Public data from three big producing states has found that some wells drilled before 2018, particularly directional wells used often in unconventional plays, may have integrity issues that could cause internal leaks.

Led by researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Energy Technology Laboratory (NETL), the new report compiled more than 470,000 regulatory records from well integrity tests in Colorado, New Mexico, and Pennsylvania on 100,000-plus wells drilled before 2018. The research was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We mined publicly available records from state regulatory databases and synthesized the results of various well testing methods into a uniform dataset that describes the integrity of 105,031 wells,” researchers said. “Our analysis of the dataset provides insight into regional well leakage frequencies in three U.S. states.”

Researchers also looked at “spatial and temporal leakage trends among vertical and directional wells, and the characteristics of leaked fluids. Our findings demonstrate the value of statewide well testing programs and highlight the challenges of interpreting disparate interjurisdictional well testing data.”

The NETL compilation provides information about ways to ensure the integrity of carbon storage, oil and gas production, natural gas storage, and hydrogen storage operations.

Stresses underground can lead to cracks in cement that hold together steel pipes. Stresses also can lead to the cement separating from the pipes. These issues may degrade integrity of the pipes, and in some cases, cause leakage.

Pennsylvania records revealed that 14.1% of wells tested prior to 2018 had potentially experienced an integrity issue. Data collected from different hydrocarbon-producing regions in Colorado and New Mexico also showed integrity issues more frequently than previously reported, DOE found.

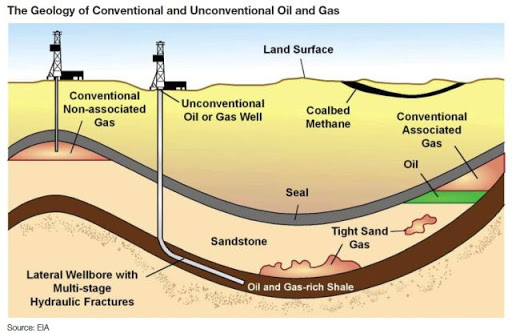

In Colorado and Pennsylvania, directional wells were more likely to experience integrity issues than vertical wells. Vertical wells are usually drilled straight to an oil and gas target. Directional wells, often used in unconventional drilling in shale and tight resource plays, often have a borehole with several targets.

Johns Hopkins University professor Harihar Rajaram of the Whiting School of Engineering was one of the authors.

“It is important to note that an integrity issue does not imply that fluids have leaked outside an oil and gas well and created a risk for groundwater contamination,” Rajaram said.

However, testing around wells for indicators that gas may be leaking into groundwater is not a widespread industry practice. According to the data, most wells that had internal leaks did not leak into groundwater.

“In Colorado most of the wells at risk for groundwater contamination are older vertical wells that were built with short surface casings that do not protect deeper groundwater aquifers that were later designated as water resources,” said Rajaram.

Rajaram added that wells with high surface casing pressures can be identified and remediated to prevent integrity issues.

“Monitoring oil and gas well integrity based on surface casing pressure or casing vent flow measurements is relatively cheap and helps to identify problematic wells early and remediate them,” Rajaram said.

There are at least 900,000 active oil and gas wells in the United States. However, accurate estimates of the percentage of wells that have experienced integrity issues during their lifetime are limited by data availability, researchers noted.

Most states require some form of well integrity testing, but the data are not publicly available. The research team recommended that future studies should continue to compile and analyze data to better inform stakeholder decision-making.